Lindsay: "Well, you get a false sense of superiority." Discussing with Lindsay whether he should try to steal Gob's underappreciated girlfriend, he bemoans: "I'm a saint, you know, a living saint. (Back in the day he had roles on "Little House on the Prairie," "Silver Spoons," "Valerie," and "The Hogan Family.") Michael wants desperately to be a good, responsible adult-and lords it over his siblings that they're not even close-but sometimes it just takes too much work. Jason Bateman, who plays Michael, is perfectly cast for this world of belated adolescence, with his boyish demeanor and sitcom-kid past. When, for example, George-Michael sees his beloved ethics teacher leaving the house one morning after a nocturnal tryst with his father, the latter kindly tries to protect his son's feelings with a fib: "Yes, your uncle Gob slept with her." That the adults' rivalries and deceptions occur in front of (and frequently involve) their own children only tightens the screws. Forced by their own indolence and incompetence to live together again (in the model home no less), the Bluth siblings recreate the painful dynamics of childhood-the selfishness, the insecurity, the competition for a parent's favor-but using the weapons of adulthood: money, sex, and a range of sophisticated lies and alliances. The genius of "Arrested Development" is that rather than present us with children who behave like adults, it offers adults who behave like children. (This latter species is so irritating and overexposed that it may yet destroy not only the family sitcom but television itself.) But for all their efforts to differentiate themselves (rich white parents with poor black kids! two dads and no mom!), family sitcoms virtually always follow the formula of loving adult caregivers watching over one or more precious, precocious kids. We've had households run by married couples and singles, by stepparents and adoptive parents, and by housekeepers of both sexes. One reason for the decline of the genre is that it typically feels played out. But even as the show revisits the family sitcom, it renews it. After a decade in which the better sitcoms largely abandoned the domestic scene to revolve instead around artificial families made up of friends or colleagues, "Arrested Development" returns to the bosom of interpersonal horror, and thus humor. With that exchange the show announces its subject matter: the family as omnipresent afterthought, frequently forgotten yet ultimately inescapable.

I thought you meant of the things you eat." As a show of support for Bluth Company, Michael and George-Michael have been living in the model home of the company's newest development, sleeping in the attic so it can remain a "pristine selling tool." As they wake up in adjacent sleeping bags one morning, Michael asks his son, "What comes before anything? What have we always said is the most important thing?" The mood of the show is set early in the first episode. Further complicating the scene is the third generation of Bluths-Michael's over-parented son George-Michael, and Lindsay's under-parented daughter Maeby. An earnest, hardworking widower with a teenage son, it falls to Michael to hold the family together: mother Lucille, the manipulative socialite older brother George Oscar Bluth II (or "Gob," pronounced Biblically as "Job"), the Segway-riding ladies' man and part-time magician younger brother Buster, the timid man-child twin sister Lindsay, the dilettante activist and her husband Tobias, the sexually ambiguous former psychiatrist and would-be actor.

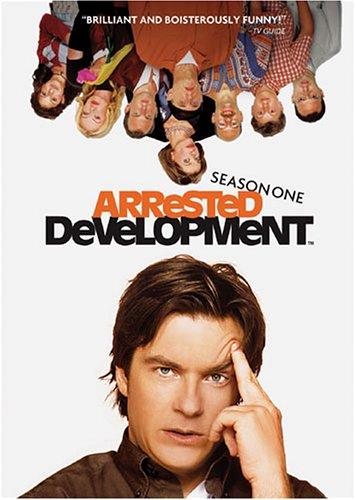

His self-involved wife and self-indulgent children have never done an honest day's work in their lives, with the exception of fortyish middle son Michael. The family in question is the Bluths, a wealthy Southern Californian clan that falls on hard times when its developer-patriarch, George Sr., is imprisoned for fraud. Put simply, this is the best sitcom on television, a biting yet somehow endearing exploration of family dysfunction. Their mere involvement with "Arrested Development"-Howard as executive producer and folksy narrator, Minelli as a self-parodic supporting character-suggests I may have given neither adequate credit.

"Arrested Development," the nearly cancelled FOX sitcom whose first season is now out on video, has made me reconsider the talents of two: Ron Howard (whom I'd written off as a purveyor of tame commercial pabulum) and Liza Minnelli (probably best if I not detail my objections). It's not often a television show can make you reconsider the talents of a longtime celebrity.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)